Taxon Attribute Profiles

Hemianax papuensis

|

Brachydiplax denticauda

|

Rhyothemis graphiptera

|

Indolestes obiri

|

Nososticta coelestina

|

Order ODONATA

Dragonflies and Damselflies

Introduction

Dragonflies and damselflies are large, strong flying insects which

have fascinated watchers throughout time. They are among the best known

insects, and because of their large size (usually 30-90 mm, but some species

are known up to 150 mm), captivating behaviour, and ease of identification

by the non-specialist, they have been referred to as "bird-watchers" insects.

Many species are territorial, and they can display complex and intriguing

behaviour. Dragonflies and damselflies are components of most riparian

ecosystems. Both adult and larval stages are predaceous, and mostly prey

upon other invertebrate species.

Taxonomy and Ecology

Synopsis of included taxa

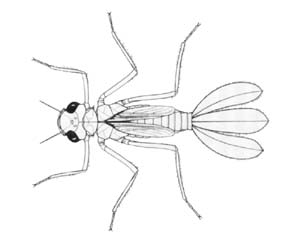

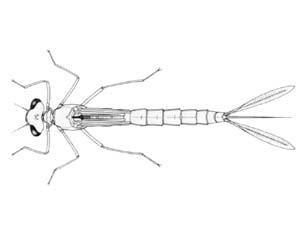

The Odonata includes two suborders: Dragonflies (Anisoptera) and

Damselflies (Zygoptera). Damselflies are smaller and more delicate, and

have the forewing and hindwing similar in shape; dragonflies tend to be

larger and stouter, and have the forewing and hindwing different in shape,

with the base of the hindwing being wider than that of the forewing. In

living specimens, the dragonflies generally rest with their wings extended,

while the damselflies rest with wings folded together over their back.

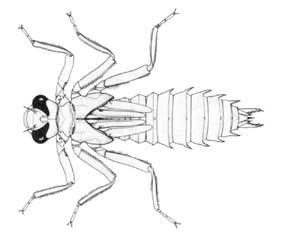

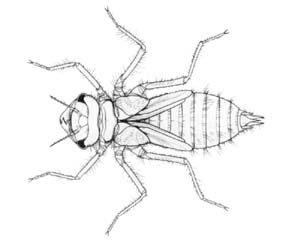

The larvae live underwater and breathe through gills. Damselfly larvae

have the gills in the form of three long appendages extending from the

tail end of their abdomen; dragonflies lack these appendages, and have

internal rectal gills.

Dragonfly larvae

Notoaeschna sagittata |

Synthemis macrostigma |

Damselfly larvae

Austroargiolestes icteromelas |

Austrolestes annulosus |

The classification of Odonata is not settled. Watson & O'Farrell

(1991) and Watson et al., (1991) list 11 families of damselflies

and 6 families of dragonflies, while the ABIF Fauna List shows 12 families

of damselflies and 18 families of dragonflies. Despite discrepancies concerning

the number of families, authors do agree that there are just over 300

species of Odonata in Australia (302 in Watson & O'Farrell, 1991;

320 in ABIF).

General overviews of Australian Odonata, including morphology, biology

and keys to the suborders and families are provided by Watson et al.

(1991) and Watson & O'Farrell (1991).

Life Form

Dragonflies and damselflies are among the best known and recognized

insects. Adults are generally large and elongate, with two pairs of large,

membranous wings which have a dense network of veins. The compound eyes

are quite large, and often occupy most of the head. Many species are quite

beautiful, with bright metallic markings on the body, or various banded

patterns on the wings. Adults are strong flyers, and are among the fastest

of all insects. The larvae are aquatic, and have elongate, prehensile

mouthparts which they use to capture their prey.

click to enlarge map

|

Distribution

Dragonflies and damselflies are widely distributed and common. Within

Australia, they are most diverse in the tropical regions of north-eastern

Queensland and Cape York. The aquatic habit of the larvae restricts reproduction

to water sources, but lone adults may be found throughout Australia, often

many kilometers from the nearest water source.

Habitat

Dragonflies and damselflies are tied to aquatic habitats. Although

the adults are free living and capable of strong flight, the other life

stages require a riparian habitat. Dragonfly and damselfly eggs are laid

in water. Most commonly, the hovering females dip their abdomens into

the water to deposit their eggs, and they can frequently be seen doing

this, either singly or still coupled to the male. Larvae spend their entire

life submerged in water, where they are predators on other small aquatic

organisms. Various species can occupy most freshwater habitats, including

waterfalls, torrents, streams, lakes, ponds, swamps, bogs and estuaries.

Cast skins of Hemicordulia tau

|

Adult emergence takes place when the larva crawls up out of the water

onto a rock or branch, firmly grasps the substrate with its legs, and

the adult emerges from the cast larval skin. Adults are strong flyers.

Males are often territorial, and can be observed returning to a favourite

perch where they observe their territory and are ready to fly out to capture

food or guard against other males.

Status in Community

Both adults and larvae are predaceous, and will be responsible for

removing numerous prey items during their life. Adults catch other invertebrates

which they eat during flight. Larval prey items are generally other invertebrates,

but larger species can take small fish and tadpoles.

Reproduction and Establishment

Reproduction

The Odonata are unusual in that the male has secondary genitalia

at the base of the abdomen, to which he transfers sperm prior to mating.

This produces a very characteristic coupling pose, where the male grasps

the female behind the head with claspers at the end of his abdomen, and

the female places the tip of her abdomen up to the base of the male abdomen.

Elaborate courtship rituals are often precede mating.

Coenagrion lyelli

|

Eusynthemis virgula

|

Dispersability

Animals which inhabit standing, often temporary, water sources often

display the ability for dispersal and migration over great distances.

Adult dragonflies are strong fliers, and even though their larvae require

water, lone adults are often seen great distances from water. This enables

them to recolonize patches of standing water that are either unsuitable

or non-existent during parts of the year.

Juvenile period

Larvae vary in habit, but all are aquatic. They can moult up to 15

times before they reach the final instar and are ready to emerge. All

larvae are predaceous, and they are generally ambush predators which remain

concealed in silt, or under rocks and plants, waiting for slow-moving

prey. Odonata larvae are unusual in having hinged, prehensile mouthparts

with strong teeth which they can shoot out to capture their prey.

Hydrology and Salinity

Salinity Tolerance

Kefford et al. (2003) reported Odonata to be more tolerant

to salinity than many other aquatic macroinvertebrates; however, Bailey

et al. (2002), Gooderham & Tsyrlin (2002) and Chessman (2003) showed

a wide range of tolerance within the group. For example, on the SIGNAL

2 grades of 1-10 (1 being least sensitive and 10 being most sensitive),

Odonata families ranged from 1 (Lestidae) to 10 (Austrocorduliidae) (Chessman,

2003).

Flooding Regimes

Alternating periods of flooding and drought could affect dragonfly and

damselfly larvae, which need water for survival. The strong flying ability

of adults will allow recolonization of aquatic habitats after periods

of drought. Several species of Australian Odonata have larvae that are

drought resistant, and can survive temporarily in an inactive state if

free water is withdrawn (Watson, 1982).

Conservation Status

Hawking (1999) reviewed the conservation status of 314 Australian

dragonflies and damselflies. Of the 314 known Australian species, 1 was

listed as Critically Endangered, 12 Endangered, 24 Vulnerable, 39 Near

Threatened, 84 Data Deficient, and the remaining 154 Least Concern.

The critically endangered species, Adams emerald dragonfly (Archaeophya

adamsi), is one of Australia's rarest dragonflies, with only 5 adults

having been captured. The species is known only from the greater Sydney

region, and some remaining habitats are under threat from development.

Hawking (1999) pointed out three major concerns: 1) the large number

of endangered species, 2) the large number of species which deserve priority

conservation action; 3) the number of species where there is insufficient

data to make a proper assessment.

Uses

Although there are no records of Aboriginal use of dragonflies or

damselflies as food, it is not unlikely that certain species were eaten.

It is well known that many insect species were eaten by Aborigines (Tindale,

1966); and the use of dragonflies and damselflies as food items in Asia

and elsewhere in the world is well documented (Pemberton, 1995; Ramos-Elorduy,

1998; Menzel & D'Alusio, 1998).

Summary

Several authors have suggested that macroinvertebrates, including

Odonata, can be effectively included in programs for monitoring water

quality (Watson, 1982; Water and Rivers Commission, 1996; Chessman, 2003;

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, 2004). Due to the variability of response

to environmental factors within the order, certain groups may be much

more suitable as bioindicator species than others. The fact remains that

they are large, easy to observe, and can be recognized by non-specialists,

making them a very suitable group for a variety of monitoring purposes.

List of MDB Species

Table 1. Odonata recorded from the Murray Darling Basin

(Classification from Houston et al., 1999).

|

DAMSELFLIES

|

DRAGONFLIES

|

| |

|

|

Coenagrionidae

|

Aeshnidae

|

|

Austroagrion watsoni Lieftinck, 1982

|

Aeshna brevistyla (Rambur)

|

|

Austrocnemis splendida (Martin, 1901)

|

Aeshna brevistyla (Rambur)

|

|

Caliagrion billinghursti (Martin, 1901)

|

Austrogynacantha heterogena Tillyard, 1908

|

|

Coenagrion lyelli (Tillyard, 1913)

|

Hemianax papuensis (Burmeister, 1839)

|

|

Ischnura aurora aurora (Brauer, 1865)

|

|

|

Ischnura heterosticta (Burmeister, 1839)

|

Austrocorduliidae

|

|

Pseudagrion aureofrons Tillyard, 1906

|

Apocordulia macrops Watson, 1980

|

|

Pseudagrion ignifer Tillyard, 1906

|

Austrocordulia refracta Tillyard, 1909

|

|

Xanthagrion erythroneurum (Selys, 1876)

|

|

| |

Austropetaliidae

|

|

Diphlebiidae

|

Austropetalia patricia (Tillyard, 1909)

|

|

Diphlebia lestoides lestoides (Selys, 1853)

|

|

|

Diphlebia lestoides tillyardi Fraser, 1956

|

Cordulephyidae

|

|

Diphlebia nymphoides Tillyard, 1912

|

Cordulephya pygmaea Selys, 1870

|

| |

|

|

Hemiphlebiidae

|

Gomphidae

|

|

Hemiphlebia mirabilis Selys, 1869

|

Antipodogomphus acolythus (Martin, 1901)

|

| |

Austrogomphus amphiclitus (Selys, 1873)

|

|

Isostictidae

|

Austrogomphus angeli Tillyard, 1913

|

|

Rhadinosticta simplex (Martin, 1901)

|

Austrogomphus australis Dale, 1854

|

| |

Austrogomphus cornutus Watson, 1991

|

|

Lestidae

|

Austrogomphus divaricatus Watson, 1991

|

|

Austrolestes analis (Rambur, 1842)

|

Austrogomphus guerini (Rambur, 1842)

|

|

Austrolestes annulosus (Selys, 1862)

|

Austrogomphus melaleucae Tillyard, 1909

|

|

Austrolestes aridus (Tillyard, 1908)

|

Austrogomphus ochraceus (Selys, 1869)

|

|

Austrolestes cingulatus (Burmeister, 1839)

|

Hemigomphus gouldii (Selys, 1854)

|

|

Austrolestes io (Selys, 1862)

|

Hemigomphus heteroclytus Selys, 1854

|

|

Austrolestes leda (Selys, 1862)

|

|

|

Austrolestes psyche (Hagen, 1862)

|

Hemicorduliidae

|

| |

Hemicordulia australiae (Rambur, 1842)

|

|

Megapodagrionidae

|

Hemicordulia intermedia (Selys, 1871)

|

|

Austroargiolestes amabilis (Forster, 1899)

|

Hemicordulia superba Tillyard, 1911

|

|

Austroargiolestes brookhousei Theischinger & O'Farrell,

1986

|

Hemicordulia tau (Selys, 1871)

|

|

Austroargiolestes calcaris (Fraser, 1958)

|

Procordulia jacksoniensis (Rambur, 1842)

|

|

Austroargiolestes christine Theischinger & O'Farrell, 1986

|

|

|

Austroargiolestes icteromelas (Selys, 1862)

|

Libellulidae

|

|

Austroargiolestes isabellae Theischinger & O'Farrell, 1986

|

Austrothemis nigrescens (Martin, 1901)

|

|

Griseargiolestes eboracus (Tillyard, 1913)

|

Crocothemis nigrifrons (Kirby, 1894)

|

|

Griseargiolestes griseus (Hagen, 1862)

|

Diplacodes bipunctata (Brauer, 1865)

|

|

Griseargiolestes intermedius (Tillyard, 1913)

|

Diplacodes haematodes (Burmeister, 1839)

|

| |

Nannophlebia risi Tillyard, 1913

|

| |

Nannophya dalei (Tillyard, 1908)

|

|

Protoneuridae

|

Orthetrum caledonicum (Brauer, 1865)

|

|

Nososticta solida (Hagen, 1860)

|

Orthretrum villosovittatum villosovittatum (Brauer, 1868)

|

| |

Pantala flavescens (Fabricius, 1898)

|

|

Synlestidae

|

Trapezostigma loewii (Kaup, 1866)

|

|

Synlestes selysi Tillyard, 1917

|

|

|

Synlestes weyersii tillyardi Fraser, 1948

|

Synthemistidae

|

| |

Archaeosynthemis orientalis (Tillyard, 1910)

|

| |

Choristhemis flavoterminata (Martin, 1901)

|

| |

Eusynthemis aurolineata (Tillyard, 1913)

|

| |

Eusynthemis brevistyla (Selys, 1871)

|

| |

Eusynthemis guttata (Selys, 1871)

|

| |

Eusynthemis tillyardi Theischinger, 1995

|

| |

Eusynthemis virgula (Selys, 1874)

|

| |

Parasynthemis regina (Selys, 1874)

|

| |

Synthemis eustalacta (Burmeister, 1839)

|

| |

|

| |

Telephlebiidae

|

| |

Austroaeschna atrata Martin, 1909

|

| |

Austroaeschna flavomaculata Tillyard, 1916

|

| |

Austroaeschna inermis Martin, 1901

|

| |

Austroaeschna multipunctata (Martin, 1901)

|

| |

Austroaeschna obscura Theischinger, 1982

|

| |

Austroaeschna parvistigma (Selys, 1883)

|

| |

Austroaeschna pulchra Tillyard, 1909

|

| |

Austroaeschna sigma Theischinger, 1982

|

| |

Austroaeschna subapicalis Theischinger, 1982

|

| |

Austroaeschna unicornis unicornis (Martin,1901)

|

| |

Notoaeschna geminata Theischinger, 1982

|

| |

Notoaeschna sagittata (Martin, 1901)

|

| |

Spinaeschna tripunctata (Martin, 1901)

|

| |

Telephlebia brevicauda Tillyard, 1916

|

| |

Telephlebia cyclops Tillyard, 1916

|

| |

Telephlebia godeffroyi Selys, 1883

|

| |

Telephlebia tillyardi Campion, 1916

|

| |

|

References

Bailey, P., Boon, P. & Morris, K. (2002) Australian Biodiversity

Salt Sensitivity Database. Land & Water Australia. http://www.rivers.gov.au/research/contaminants/saltsen.htm

Chessman, B. (2003) SIGNAL 2 - A Scoring System for Macroinvertebrate

('Water Bugs') in Australian Rivers, Monitoring River Heath Initiative

Technical Report no 31, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

http://www.deh.gov.au/water/rivers/nrhp/signal/

Gooderham, J. & Tsyrlin, E. (2002) The Waterbug Book: a guide to

the freshwater macroinvertebrates of temperate Australia. CSIRO Publishing.

Hawking, J.H. (1999) An evaluation of the current conservation status

of Australian dragonflies (Odonata). Pp 354-360, in: W. Ponder &

D. Lunney (eds), The Other 99%. The Conservation and Biodiversity

of Invertebrates. Transactions of the Royal Zoological Society of

New South Wales, Mosman.

Houston, W.W.K., Watson, J.A.L. & Calder, A.A. (1999) Australian

Faunal Directory: Checklist for Odonata. Australian Biological Resources

Survey, Department of the Environment and Heritage. http://www.deh.gov.au/cgi-bin/abrs/abif-fauna/tree.pl?pstrVol=ODONATA&pintMode=1

Kefford, B.J., Papas, P.J., Nugegoda, D. (2003) Relative salinity tolerance

of macroinvertebrates from the Barwon River, Victoria, Australia. Marine

and Freshwater Research, 54: 755-765.

Menzel, P. & D'Alusio, F. (1998) Man Eating Bugs: The Art and Science

of Eating Insects. Ten Speed Press, Hong Kong.

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (2004). Wetlands: Monitoring Aquatic

Invertebrates. http://www.pca.state.mn.us/water/biomonitoring/bio-wetlands-invert.html

Pemberton, R. W. (1995) Catching and eating dragonflies in Bali and

elsewhere in Asia. American Entomologist, 41: 97-102

Ramos-Elorduy, J. (1998) Creepy Crawly Cuisine: The Gourmet Guide to

Edible Insects. Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont.

Tindale, N.B. (1966) Insects as food for the Australian Aborigines.

Australian Natural History, 15(6), p. 179-183.

Water and Rivers Commission (1996). Macroinvertebrates & Water

Quality. Water Facts 2. http://www.wrc.wa.gov.au/public/waterfacts/2_macro/WF2.pdf

Watson, J.A.L. (1982) Dragonflies in the Australian environment: taxonomy,

biology and conservation. Adv. Odonatol., 1: 293-302.

Watson, J.A.L. & O'Farrell, A.F. (1991) Odonata (dragonflies and

damselflies). Pp. 294-310, in Insects of Australia: A textbook for students

and research workers. CSIRO. 2nd Edition.

Watson, J.A.L., Theischinger, G. & Abbey, H.M. (1991) The Australian

Dragonflies: A Guide to the Identification, Distributions and Habitats

of Australian Odonata. CSIRO.

|